Guide

What diamond criteria to favour ?

In 1919, M. Tolkowsky, physician and mathematician, published a study on the optical properties of the round brilliant diamond cut. He suggested angles, optimal proportions. These (updated) values are nowadays referred to as the diamond cut grade, noted in certificates. It is the first variable parameter which will determine the beauty transmitted through the fixed data (clarity, colour), and nowadays people tend to attach great importance to it.

Cut Grade

EX excellent | VG very good

G good | F fair | P poor

Polish Grade

EX excellent | VG very good

G good | F fair | P poor

Symmetry Grade

EX excellent | VG very good

G good | F fair | P poor

| Cut Grade | Excellent | Very Good | Good | Fair | Poor |

| Polish Grade | Excellent | Very Good | Good | Fair | Poor |

| Finish Grade | Excellent | Very Good | Good | Fair | Poor |

Engagement ring

4 Claws Classic

Solitaire diamond with 4 claws, a classic and timeless style. The highlighting of the diamond…

Ring

BRILLIANT

The perfect gift for your ever lasting love. Hand made french jewellery. Gold 750/000. Delivered in…

Pendant & Necklace

4 CLAWS

4 claw diamond pendant without bail. Forçat chain fixed by 2 rings on each side of the…

Wedding Band

RUBAN

Classic diamond wedding ring. 18 carats gold. Made in France. Delivered in a jewellery box. See…

Earrings

4 CLAWS CRADLE

Handmade diamond earrings, 4 claws heart-shaped cradle setting. Elegant exclusive design by…

Bracelet

ETERNITY

Diamond bezel bracelet. Very popular, a style that is both classic and contemporary. 18 carats…

Engagement ring

5 Claws Classic

Solitaire diamond with 5 claws. Solitaire offered in 18k white, yellow or pink gold (750/000) or in…

Ring

PRINCESS ROYAL

Style full of sparkle without being ostentatious. The dawn of passion and romance. Hand made to…

Pendant & Necklace

3 CLAWS B

Diamond pendant with 3 claws to enhance the stone as much as possible. Crimping carried out with…

Wedding Band

NOCEA

A modern style: diamonds are entwined in a crimped said "rail", a very contemporary…

Earrings

3 CLAWS PREMIUM

Handmade earrings with diamond belt based on mid height of the claws which are based on a rabbet.…

Bracelet

ERGO

Very modern, bright without being ostentatious. Pleasure of playing with the brilliance of…

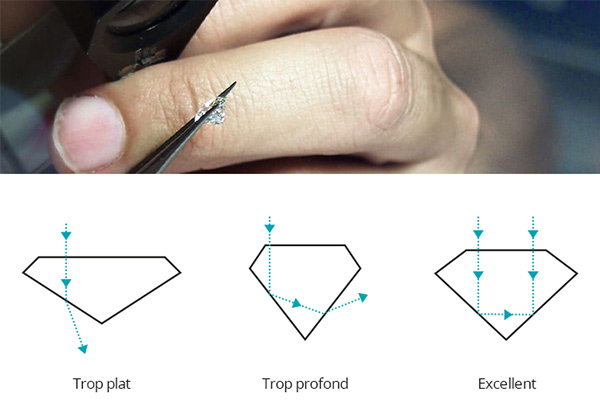

The diamond is a light accumulator. When a diamond is cut according to good proportions, qualified as cut grade, the light remains imprisoned and reflects itself from one facet to the next, exploiting the diamond’s refraction property to the maximum, and it then comes out again through the top (the table). A diamond that deviates from the ideal proportions lets part of the light escape through its table.

The proportions defined by the cut grade determine the fire and the brightness (light return), the scintillation of the diamond. It is the most important criteria. The finish grade qualifies the divergences in the symmetry of the diamond cut shape, the facets and the quality of the polish.

These criteria are often ignored. We attach the greatest importance to them: all our diamonds are exclusively “excellent”, “very good” or “good”. Diamonds of a “medium” or “bad” quality convey the choice of favouring weight instead of the quality of the diamond cut.

The girdle is the circumference of the diamond, which will be used to fix the diamond in the jewel. The thickness of the girdle enters the qualification of the proportions (avoid girdles described as “very thin” or “very thick”).

The exterior aspect of the girdle (polished or facetted) does not enter the qualification. You often find what are known as “natural facets” in the girdle, they are proof of the original rough stone.

There are no established or generally accepted rules, but take note, however, of the following criteria and how they differ from the brilliant round diamond cut:

Renowned as an extremely precious material, ideal for the manufacture of luxury jewellery, diamonds only reveal the full extent of their brilliance when they are worked and cut. Together we will retrace the history of its cut, the multitude of shapes given to the diamond over the centuries, according to successive modes, in line with the evolution of the know-how of diamond dealers, which today makes it possible to obtain pieces of exceptional quality.

Very early in the history of mankind, diamonds were exploited by ancient civilizations. But it was only later that its cutting really began. Indeed, it was not until the end of the 14th century that the diamond began to be worked, only on its outer part, in order to give it more brilliance, by flattening its surfaces.

Here is a picture of an old cut diamond, with an open breech and a limited number of facets on the pavilion (under the crown). For more information, see the explanations further down on this page.

During the Renaissance and at the beginning of the modern era, jewellers gave diamonds a very basic table shape, with few faces, in pink, or a pointed shape. The number of these gradually increased, and they were worn until thirty-two at the end of the 17th century, with a cup known as a Mazarin cut, named after the famous Regent of France.

The technique used by diamond dealers, particularly from Bruges and Burgundy, from the beginning of the 15th century onwards, enabled the diamonds to be cut using a porous cast iron grinding wheel.

The 1720s saw the rise of an interest in jewellery by aristocrats and the upper bourgeoisie, with the arrival of Brazilian diamonds, which partly replaced Indian mines. Diamonds were encrusted in a metal setting and coupled with other precious stones, most frequently emeralds. However, the shapes given to diamonds change very little: innovation is more in the composition of the jewellery.

New mines in South Africa and then Australia are bringing impressive quantities of diamonds to Europe, and more specifically to the United Kingdom. Although knowledge of the properties and composition of diamonds is becoming increasingly precise, thanks in particular to Lavoisier's work, cutting is not revolutionising in the strict sense of the word.

Nevertheless, the support is evolving, the metal back is being abandoned for a setting in gold grains: the ornaments and jewellery present exotic, floral shapes, sometimes of ancient inspiration.

As in many areas of craftsmanship, the industrial revolution and globalisation during the 19th century brought about long-term changes in the very way in which diamonds were worked. More modern tools and more varied samples are at the disposal of jewellers, while science allows a better understanding of the cut.

In the 1870s, a British man, Cecil Rhodes, took part in the explorations of South Africa and soon saw the possibilities offered by this still wild territory. The abundant diamond resources were exploited in the years that followed. Cecil Rhodes founded the De Beers company in South Africa and soon began exporting to Europe, with two flagship destinations: London, for British customers, and Antwerp, home to some of the best gemstone cutters of the time.

The arrival of De Beers on the international market marked a turning point, due to the monopoly that its managers (Cecil Rhodes, then the Oppenheimer family) managed to establish. Antwerp, which had long been a stronghold of trade and finance, gradually became the world city of diamonds from 1886 onwards.

It was in this city that the development of modern diamond-cutting techniques and standards took place. Moreover, Antwerp still accounts for 70% of the diamond market today.

The classical diamond shapes, more or less fixed since the end of the 17th century, have undergone significant diversification during the 20th century. From 1919 onwards, the round brilliant cut appeared, which was created by the Belgian diamond dealer and engineer Marcel Tolkowsky, a native of Antwerp. With 56 facets plus the table, round brilliant diamonds reach a previously unknown form of perfection.

Diamond working then enters a more scientific era, the cutting procedures incorporate mathematical elements to optimise the brilliance of the stone. The second half of the 20th century saw the arrival of competitors to the De Beers company, and questioned its monopoly: countries such as Russia, Australia, but also Canada.

The technique was also perfected, and the use of a phosphor bronze disc, enriched with diamond powder, became widespread for sawing, one of the major stages of cutting.

N.B.: Note the open breech, unlike the modern size (below) where the breech is in closed point. The number of facets is also lower on the old size. The modern cut has many more facets on the pavilion (area under the table and the crown of the diamond).

Nowadays, there is an abundance of possible shapes. Here we will content ourselves with the ten most important ones, which make up the vast majority of diamond cuts. It is worth noting, on the other hand, the recent use of the laser, which makes it possible to work with greater precision and efficiency than traditional tools, and to obtain shapes that were previously impossible.

As mentioned above, the round brilliant has been an extremely prestigious type of diamond for a century and is currently the most sought-after by customers. It is characterised by a circular, multi-faceted upper part and a conical lower part (the breech). Its shape is generally the one most commonly used in the illustration and common representation of diamonds in jewellery, making it an almost absolute standard in the field, and accounts for three-quarters of world sales.

Certainly the second most common type, the princess cut diamond can be recognised by its square appearance, often used for engagement and wedding rings. Its name alone adds to the magic of the diamond!

More rectangular than the princess cut, the emerald diamond relies on the symmetry of its lines, as well as on the relief effect emanating from it. This shape is reputed to enhance the purity of the gemstone and is ideal for a ring. The ideal length/width ratio is around 1.4 according to many specialists, and can vary from 1.25 to 1.75 depending on the properties of the different stones.

In the shape of a drop of water, the pear-shaped waistband stands out by its unique tip and is mostly found on rings or necklaces. Halfway between the round and marquise shapes, its elegance is guaranteed if it is optimally symmetrical. A length/width ratio of 1.40 to 1.70 is recommended for this type of jewel.

This form can be considered traditional in jewellery, in the sense that it was one of the first from a historical point of view. However, modern cushion diamonds are more faceted and have a much higher brilliance than their ancestors.

Often square or slightly rectangular (length/width ratio 1.10), its proportions are reminiscent of princess diamonds, but with rounded contours, the cushion cut is still popular today. It has even become very fashionable again in recent years.

By the quality of its shine, it comes close to the characteristics of the round brilliant cut, while its shape can sublimate long fingers. The most classic ratio between length and width varies from 1.30 to 1.50. Its shape gives the diamond the visual impression of a larger surface area than the standard brilliant, while remaining light.

Slightly rectangular, the radiant cut and its many facets (70 in number), appears as a happy medium between princess and cushion diamonds, with an octagonal outline. The radiant diamond has a brilliance that experts consider superior to that of emerald diamonds. A length/width ratio of 1.05 makes it an ideal jewel.

Developed in 1902 by the Asscher brothers, famous Dutch diamond dealers, the eponymous cut has 74 facets and a square shape with an octagonal effect. Its lower part, or breech, is cut with rectangular facets. Asscher diamonds, which were highly prized in the inter-war period, are now becoming a little more fashionable again.

Can there be a stronger symbol of love than a ring set with a heart-shaped diamond? For this fancy cut, symmetry is obviously essential, as is the design of the point. If the shape needs to be highlighted by the diamond dealer, you have the choice of proportions: will you prefer a large heart, or on the contrary stretched, or a length/width ratio of 1.00? The latter is one of the most widespread and harmonious.

This shape would take its name from a diamond cut for the Marquise de Pompadour in the 18th century. Marquise diamonds are distinguished from ovals by two pointed ends, which require precision work. This type of cut produces a diamond with 55 facets, for a classic length/width ratio that can vary from 1.75 to 2.25. Like oval diamonds, they are suitable for long, thin fingers, while giving the illusion of a larger surface area.

Before reaching the final result, and obtaining a real brilliant and cut diamond, ready to be set, four main steps are necessary: cleavage, sawing, roughing and faceting. In order to fully understand the way in which the diamond is worked, it is necessary to detail these successive operations.

This is an ancient technique for cutting diamonds: cleavage consists of making a notch with another diamond and then separating the first diamond in half with a blade. As with wood, there are angles at which a diamond can split relatively easily in four directions.

This is undoubtedly the longest stage: diamonds are the most resistant mineral and it takes many hours to work on them. In the past, the sawing process was carried out using a wire or brass wire, but nowadays it is carried out using a bronze disc, which rotates at 5500 rpm. Despite this, the sawing process is still very slow, at a rate of one millimetre per hour, which is nevertheless much faster than in the early days of diamond cutting.

Previously done entirely by hand, this process is a preliminary step to faceting. Rough cutting consists of rounding the surfaces of the rough diamond, giving it a first shape, both for the upper part (the table) and the lower part (the breech). The first step in rough cutting is carried out using a machine, a mechanical lathe in the middle of which a lower quality diamond is fixed, against which the craftsman will come and apply the diamond to be worked, set at the end of a stick, using cement.

Once the roughing is completed, it will be time to move on to the final stage of cutting, which will give the diamond its multiple facets and reveal its full brilliance potential. It is at this point that the use of the porous cast iron grinding wheel coated with diamond powder, already in use during the Renaissance, will be necessary. A final polishing of the facets obtained will complete the cutting of the diamond, which will then be ready for marketing.

French jewellery

Our slogan

Passion, Authenticity, Expertise

Certified diamonds

By 3 world-renowned laboratories

Exceptional quality of stone and jewel

Customer service at your service, provided by diamond dealers

Sealed diamonds with a certificate of quality and authenticity

French manufacturing

30-Day « satisfied or reimbursed »

guarantee

Online secured payment

De Hantsetters, diamonteers since 1888

Customer service at your service, provided by diamond dealers

All our diamonds are independently certified by 3 world-renowed organisations

Want to talk to a diamonteer ?

Contact us nowAs you continue your navigation, you accept the use of cookies to provide our service and to secure transactions on our website.

Don't show anymore More info